‘L’objet le plus triste du monde ? Je crois que c’est un violon brisé. En tout cas, c’est la vue de la boîte à violon écrasée sur la route, avec les cordes de l’instrument s’en échappant, qui m’a le plus serré le cœur. Elle symbolisait l’accident plus encore que la jeune femme étendue en bordure du fosse, les doigts griffant la terre sèche et les jupes relevées sur des cuisses admirables.’

“The saddest thing in the world? I think it’s a broken violin. Certainly, seeing the violin case smashed on the roadway, with the instrument’s strings coming out, is what touched my heart most. It said ACCIDENT more strongly than the young woman stretched out on the side of the ditch, her fingers scratching the dry earth and her dress flopped up to show off her admirable thighs.”

— Frédéric Dard, Le bourreau pleure

What a rare treat it is to pick a book in a foreign language at random from a shelf in a friend’s mother-in-law’s home and read a first sentence like that one. I immediately asked to borrow it and finished the book on the bus ride home. (or

The Executioner Cries) is from 1956, and reads like Jim Thompson’s

The Getaway, set in Spain.

On a languorous Spanish vacation, the narrator runs over this girl, then fetches her back to his hotel. She recovers quickly from the accident. She turns out, however, to be amnesiac and can’t remember her name, who she is, or what she was doing in Spain, since she speaks French like a native. The narrator promptly falls in love with her and vice versa. Who is she? He traces her through the labels of her clothes to a suburb of Paris, discovers her identity and her past, and then, in best Thompson fashion, exits his own relatively conventional life to join her in the kind of twisted existential misery that could sour you permanently on the notion of “following your heart.”

On a cursory check, I don’t see

Le bourreau pleure ever having been translated into English. Dard is best known for his San-Antonio series of spy novels, but this one also is still in print, fifty years after initial publication.

Fortuitously, I recently read

this intriguing guide to how to write a novel in a weekend, authored by the legendary

Michael Moorcock, famous for his Elric of Melniboné sword-and-sorcery novels and his bizarre and genre-defying Jerry Cornelius novels. Having last picked up a Moorcock when I was in high school, back in the 20th Century, I recall them as being completely impossible to understand or remember after having read, but lots of books are like that to me (a reason why I have such trouble working on this blog; imagine finding books to care about, week after week). Still, you have to give the fellow credit for figuring out a pretty simple formula for novel-writing.

The entire way through the Dard book, I am thinking of how it pretty much fits the model of the Lester Dent master pulp-novel formula, which Moorcock lovingly describes. You could call

Bourreau formulaic, with the proviso that Dard uses the formula to the same frightening effect that Thompson did. Take the novel as a metaphor for life. Then reduce the novel to a formula, as in classic Lester-Dent pulp fiction. That’s life as we live it, most of us, according to a formula: one cup oatmeal, three cups coffee, and $2.25 for the subway to work.

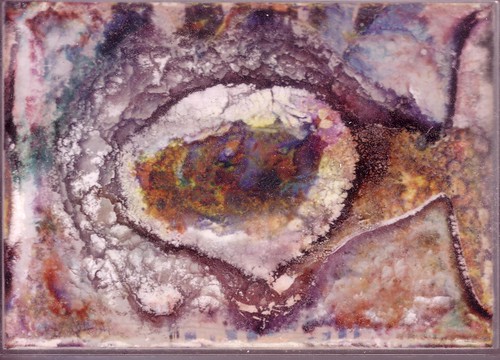

Dard’s couple ends up fleeing to a broken-down old house outside an anonymous Spanish town, in a setting that resembles a

Krazy Kat comic strip:

The loneliness of the place had something depressing about it. It didn’t exactly resemble Spain; rather it was like the Australian desert, something flat and infinite, with low, flat, black trees. Whose idea was it to have built such a tumbledown house in this desolate spot?…At that moment, I couldn’t stop thinking that if Hell existed, it would resemble where I was now living.

My question is this: who is really living in Hell, the character or the reader? Bourreau comes to its conclusion too soon afterward for the answer to be resolved.